Seeking an Ideal Third Spot? Consider a Garden as Your Option

In the heart of cities and suburbs, gardens have emerged as powerful tools for building healthier and more connected communities. These vibrant, green spaces, often staffed by volunteers, serve as **third places**—social environments outside of home and work—that foster community building and social interactions.

The concept of a third place was introduced by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his book "The Great Good Place." These are settings where people meet old friends and make new ones, ideally located close enough for easy walking distance. Gardens, cafes, and pubs are prime examples of third places, offering a cozy and inviting atmosphere for socializing and building communities.

Gardens, especially community gardens, bring together diverse neighbors who might not otherwise meet, facilitating meaningful conversations and cooperative activities like gardening. This interaction nurtures friendships and enhances the social fabric of neighborhoods, promoting a sense of belonging and community cohesion.

As third places, gardens offer regular, informal opportunities for people of all ages and backgrounds to engage without pressure. This helps reduce social isolation, a known factor for depression and anxiety, by enabling people to form friendships, share experiences, and gain a true sense of belonging.

Gardens also foster intergenerational and cross-cultural exchange. Older adults can share traditional knowledge and skills with younger generations, while children and youth introduce new sustainable practices. This dynamic exchange bridges age gaps, preserves agricultural wisdom, and strengthens communal ties across generations.

Managing and maintaining a community garden requires collaboration, communication, and conflict resolution, which help develop leadership and social skills among participants. Gardening projects often involve group decision-making and coordinated effort, enhancing social capital in communities.

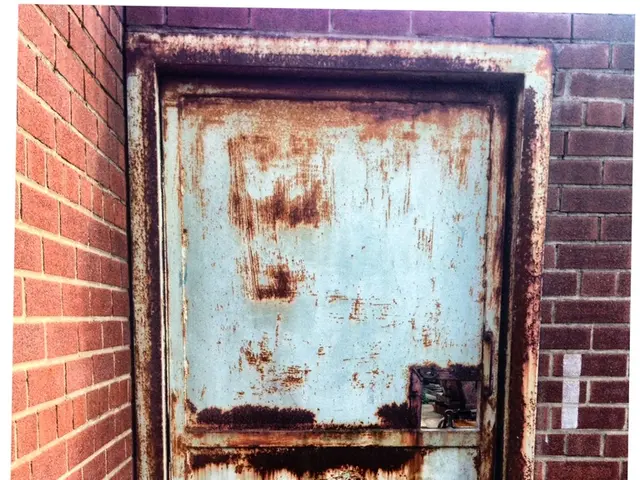

Moreover, gardens transform vacant lots or unused areas into vibrant, green, restorative spaces that provide psychological benefits and respite from urban stress. These natural settings encourage people to spend time outdoors, interact socially, and feel more connected to their environment and each other.

By occupying and beautifying previously neglected or crime-prone areas, gardens reduce opportunities for criminal activity and contribute to community redevelopment, enhancing overall neighborhood safety and pride.

Teo Spengler, a master gardener and docent at the San Francisco Botanical Garden, has studied horticulture and written about nature, trees, plants, and gardening for over two decades. With experience gardening in a range of climates, having been raised in Alaska and currently splitting her life between San Francisco and the French Basque Country, Spengler is a testament to the versatility and adaptability of gardens as third places.

In conclusion, gardens as third places uniquely combine social, environmental, and psychological benefits that strengthen community bonds, foster social inclusion, and encourage active participation, making them powerful tools for building healthier and more connected communities. Whether you're a new resident looking to connect or a long-time resident seeking social interaction, gardens offer a welcoming and inclusive space for all.

[1] Oldenburg, R. (1989). The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through the Day. New York: Touchstone. [2] Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [3] Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (1993). The Biophilia Hypothesis. New York: Wiley. [4] Ulrich, R. S. (1984). The Environmental Psychology of Gardens. In L. H. Cullen, M. J. Fisher, & S. R. Kaplan (Eds.), Humanscapes: Architecture, Planning, and the Human Environment (pp. 173-191). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Gardens,being prime examples of third places, offer opportunities for intergenerational and cross-cultural exchange through shared gardening activities. This cultural exchange nurtures a sense of community and enhances the vibrancy of home-and-garden spaces, making them an integral part of the lifestyle and social fabric of neighborhoods.

Managing and maintaining a garden as a third place requires the development of leadership and social skills, such as collaboration, communication, and conflict resolution. Gardening projects, being cooperative in nature, provide an avenue for fostering a healthier and more connected lifestyle within the community.